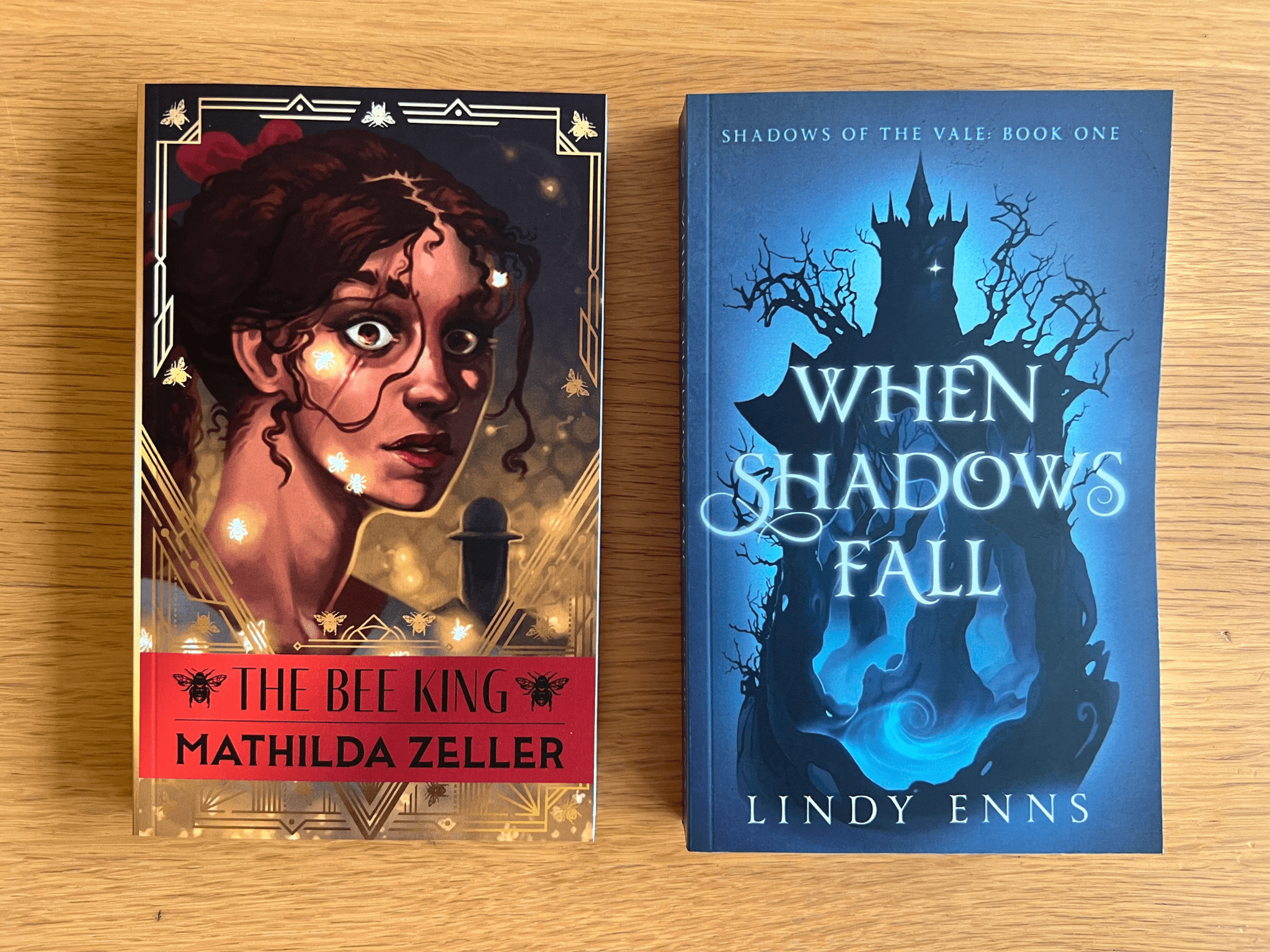

Our Second Writing Competition

Our Second Writing Competition

Your submissions get better every time, we're beyond grateful for everyone who participated! These are the top five, with Moon Island by Collin Lowe being the winner.

We've made a change and will now be hosting these competitions every three months, stay tuned!

We found a boat on the beach by the cave.

Half buried in the sand, the bottom was stripped out and scratched, as though it had hit some profoundly rocky reef on its way in.

I wondered if, perhaps, this might be our ticket home.

It was a smallish thing, with a single cracked mast. The ocean’s wrath had all but stripped away the rigging and what was left of the sail hung in scraps and tatters. Still, we decided it would have to do. It wasn’t that we had much faith in the affair, but we knew that if we stood a chance of escaping the moon-shaped island, this was as good as a written invitation.

Nothing more interesting had washed ashore in the last year. And we were all but certain that nothing of greater interest was going to, either.

The great sheafs of garbage that had tided us over in the first year had steadily dried up over time. Now, the sea delivered us scarcely more than clumps of seaweed and scraps of shells. As our fishing pools offered less fish and crabs these days, we knew that the time had come.

We took great care in the number of trees we procured from the grove for our project. The island had few to offer us, but enough that we could squeeze out a handful of flat planes to replace the bottom of our vessel.

The rigging was less tricky. There were plenty of vines and grasses from Moon Island, and what it could not provide the sea was happy to offer on our shores.

The sail was a sacrifice unlike the others. We had no tools to craft something suitable, so what few clothes we had to spare we sewed together with the emergency kit.

We couldn’t call it a suitable vessel by any means. I wasn’t even sure if we could call it seaworthy. But to me, it looked like the last lifeline home: back to a forgotten life that had passed us by.

We loaded our new ship with everything that we had washed ashore with and everything we had gathered and prepared during our stay: dried foods, a time-worn cooler, coconuts hollowed out and filled with fresh water, a couple of sleeping bags, and more. Then, we pushed the ship out to sea and climbed aboard, unfurling our sail and catching the wind.

I had never been so happy to say my goodbyes to dry land before.

The first few nights were peaceful. The ocean rocked us gently in her arms, swaying us to sleep. But by the fourth night, angry clouds with puffy, dark crowns gathered in the skies and the waves grew choppy.

The storm hit on the sixth night and lasted for three days straight.

On the storm’s third day, the waves swallowed our ship into the ocean’s hungry belly, throwing the vessel’s hull onto sharp rocks.

When I came to, my face was sticky with seawater and plastered with sand. The ocean released her hold of us, pushing us up onto the beach of a moon-shaped island.

We began the painstaking process of preparing for what it might take to survive on this new island: investigating the tide pools for fish and building traps, finding a source of fresh water and patching up the hut we found.

Over the next few months, the tide brought in an assortment of garbage that we gathered in case it might be of use to us. I was particularly excited by a time-worn cooler that drifted in which we hauled up to our hut in the heart of the island.

One day, we found a boat on the beach by the cave.

Half buried in the sand, the bottom was stripped out and scratched, as though it had hit some profoundly rocky reef on its way in.

I wondered if, perhaps, this might be our ticket home.

At the harbour, there’s a rule: Don’t shout at someone who’s docking, their hands are already full.

I broke that rule when we were trying to love each other.

I kept yelling, “Straighter! Slower! No, not like that!”, forgetting that docking is the hardest part, and we were both gripping the same ropes with our hands burning.

Later I realised the harbour rules were ours, too.

Rule 1: Keep your weight low and centred.

In a small boat, if you stand too quickly or lean too far, the whole thing tips. I mistook standing tall for sailing well, believing in grand gestures, planning futures, or rushing forward.

But real love was always lower, steadier, and ordinary: breakfasts that weren’t special, walks that led nowhere, and the simple texts between us.

If I could redo one thing, I would sit more. I’d take my weight off your nerves. I’d let the ordinary keep us upright.

Rule 2: Look where you want to go, not at what you’re trying to avoid.

It’s so easy to fixate on the rock and steer straight into it. I spent hours avoiding the fight, the fear, the “too much” of me, the “too little” of you, and in doing so, I kept my eyes on all of it.

You can’t navigate by not. You have to name a shore and head there. We never picked a shore out loud. Maybe that’s why we drifted into everything we swore we wouldn’t be.

Rule 3: Check the bilge on sunny days.

Bilge water gathers quietly. You only hear it if you stop and pay attention.

Our bilge was silent, the kind that feels safe until it suddenly isn’t. I told myself we were fine because the sky was pretty. You told yourself the same. By the time the pump kicked on and wouldn’t stop, it was already too late.

If I could go back, I’d ask smaller questions sooner: Are you tired? Do you feel alone next to me? Where is the small leak?

I wouldn’t have waited for the storm to prove we were sinking.

Rule 4: Split the watch.

At sea, one person sails while the other rests. That rhythm keeps you sane.

When you steered, I stood behind you, scanning the horizon over your shoulder. When I steered, you rechecked the chart. I re-tied your knots when you weren’t looking. You let me, and stopped asking me to sleep.

If I love again, I’d do less. I’d sleep when you steered. I’d trust the boat to hold steady under your hands, and let you trust it under mine.

Rule 5: Carry oars, even if you have a motor.

We liked the hum of speed. We loved believing momentum itself could keep us safe. That if we kept moving fast enough, nothing could catch up with us.

We kept speeding until the motor coughed: the busy week, the missed calls, the night we forgot how to be kind. Then we had no quiet way to move forward once the noise stopped.

I should have packed oars. I should have said, “Let’s go slow. Let’s row. It will take as long as it takes.” I should have traded speed for steadiness. That might have saved us.

Rule 6: Wave at other boats.

There is a small courtesy on the water: wave at other boats because we are all on something that can flip.

We forgot to wave. We acted like no other boats struggled, when they did, just the same.

I wish we’d waved more to friends, to family, even to the strangers who could have said, “We were stuck in dead calm. We took on water. We waited. And it wasn’t the end.”

It didn’t have to end us, either.

Rule 7: Name the wind without blaming it.

Winds change. They rise, they fall. It doesn’t mean you’ve steered badly, it only means the weather turned. You trim the sail, or you drift, or you drop anchor and wait.

We treated every calm like it was proof we’d failed. We punished ourselves for bad weather we couldn’t control. But there was nothing to punish. There was only us, trying.

These are the rules I learned the hard way. I’m trying not to carry their weight anymore. I’m learning to set them down so I can sail again with less ballast. Think of this letter not as a flare, not even as an apology, but as a logbook entry. It says: I’ve been at sea, and I’ve taken notes. Some lessons came too late, others came just in time to write down.

I don’t know if we’ll ever share a deck again. But if you ever read this, and you are happy, know that I am glad you found a boat steady enough for you. If you read it while you’re stuck between harbours, know that you are not the only person on the water tonight. Somewhere, another boat is drifting too, its sailor learning patience instead of panic.

I am learning to do that too. I sail slower now. I carry oars. I wave.

And if we, someday, find ourselves on the same dock, let’s put our weight in the centre. Let’s split the watch. Let’s call the wind by its name and not by our fear.

Let’s not shout while docking.

Because my hands were full. And yours were, too.

The problem with being eternally damned to sail a haunted galleon is not the existential dread or the fact that grog tastes like ash. No, the real problem, Captain Shivers ‘Shiv’ Marrow reflected, was that his dog was currently using his beloved eyepatch as a chew toy while leading the entire crew on a merry chase across the deck of The Spectre.

“CANNONBAIT! YOU INFERNAL FLEABAG! GIVE THAT BACK!” Shivers roared, his voice a jovial thunderclap that did little to convey his rising panic. Without the patch, the pulsating, fleshy, soul-snaring parasite in his left socket twitched in the open air, making his good eye water with sympathetic horror.

Cannonbait, a delightful clatter of bones held together by pure, unadulterated mischief, merely yipped, the precious eyepatch with the embroidered ‘S.M.’ flapping from his jaw like a captured flag. He skittered past Breakbone, the ship’s mountain of a brute.

“I got ‘im, Cap’n!” Breakbone bellowed, lunging with the grace of a falling wardrobe. He promptly tripped over a stray cannonball that had plopped uselessly onto the deck last Tuesday, slid headfirst into a barrel of spare femurs, and emerged wearing a ribcage for a hat. “Just a tactical reposition, sir!”

The hound, wagging his tailbone with glee, bounded up the rigging.

“Wobblebones, you coordinate this chase!” Shivers commanded from the deck, pointing a bony finger upward.

From the crow’s nest, Navigator Wobblebones squinted his one perpetually half-closed socket, holding a map of the ship itself upside down. “According to my calculations, the canine is heading…inland!”

The ship’s ropes, sentient and eternally bored, decided to join the fun. One snaked out and gave Wobblebones a friendly but debilitating wedgie. Another lassoed Breakbone’s ankle, hoisting him upside down, where he dangled like a clumsy piñata.

Cannonbait clattered back down to the main deck, dodging the flailing Breakbone and making a beeline for the cargo hold.

“Fear not, Captain!” Quartermaster Rattlejaw announced, blocking the hatchway. He was a firm believer that any problem could be solved with a sufficiently long-winded anecdote. “I shall reason with the beast. Cannonbait, my dear boy, this reminds me of a time in Archmouth when a capuchin monkey made off with my favorite child-sized glove. A fascinating story, really. It all began with a dispute over a burlap sack of what I thought were horseshoes, but were in fact…”

Cannonbait, utterly un-fascinated, zipped between Rattlejaw’s legs and vanished into the darkness below.

“He’s headed for the necromancer!” someone shrieked.

Down in the hold, surrounded by useless junk and the faint smell of ozone, Ljuboš was in the middle of a very important ritual. He was chanting furiously at a rubber chicken while sprinkling it with diamond dust. “By the shadows that bind, by the pact I have made, you shall… uh… become slightly more rubbery!”

Cannonbait burst into the scene, slid on a puddle of spilled incense, and crashed directly into Ljuboš, sending a cloud of expensive dust into the air.

“Aha!” Ljuboš declared, covered in glitter. “My paralysis spell is a success! He is momentarily stunned by my arcane might!”

Cannonbait sneezed, shaking the glitter from his skull, and trotted off with the eyepatch toward the galley, leaving the necromancer to meditate on his victory.

The galley door swung open to reveal Chef Gruelguts, a horrifyingly cheerful skeleton stirring a cauldron of bubbling, iridescent stew. The smell alone could stun a kraken.

“Ah, the guest of honor!” Gruelguts beamed. “Little doggy must be hungry after all that running. Come, have a taste of my seven-week-aged Fin Rot Bisque! It’s what caused the curse, you know. Malnutrition! One bite of this and you’ll be too full of protein to run!”

Cannonbait took one sniff, gagged audibly—an impressive feat for a creature with no lungs—and bolted. First Mate Vincent van Bone, leaning against the mast with his hook hand polished to a gleam, watched the whole procession with an expression of profound apathy. He hadn’t moved an inch.

The chase finally culminated on the bowsprit, with the rascal cornered, the churning, misty sea below him. The crew gathered, a clattering mob of useless degenerates.

“Alright, lad,” Shivers said, approaching slowly, his voice uncharacteristically gentle. “Hand it over. No more games.” His cursed eye pulsed, its malevolent red glow casting an eerie light on the scene.

Cannonbait tilted his head, then dropped the eyepatch. It tumbled through the air in slow motion. The entire crew gasped, a sound like a thousand maracas falling down a flight of stairs. It was Pollywog, the terrified cabin boy and the only seemingly sane person aboard, who scrambled out onto the bowsprit and caught it just before it hit the waves.

He handed it back to the Captain with a trembling hand. Shivers took it, his usual grin returning to his face.

“Thank ye, Pollywog,” he boomed, turning to his crew. “A fine bit of morning exercise! It gets the blood pumping! Or, well, the marrow rattling!” He let out a hearty laugh. “Now, what do you say to a celebratory ration of grog?”

He winked with his good eye at Pollywog, then finally secured the eyepatch over the baleful, fleshy orb. The crew cheered, their short-term memories as faulty as their sailing skills.

As the mob dispersed, Pollywog sidled up to the Captain. “Sir? Why did Cannonbait take it?”

Shivers looked down at the hound, who was now contentedly gnawing on Ljuboš’s rubber chicken. He lowered his voice. “Because, lad, that cursed eye of mine gets jealous. If it’s uncovered for too long, it starts trying to stare my good eye into submission. The patch keeps the peace.” He patted his eyepatch conspiratorially. “It’s a delicate internal diplomacy, you see.”

Pollywog stared, his jaw slack. On The Spectre, even the madness had madness. Shivers just laughed, a sound that rolled across the cursed waves, as Cannonbait yipped happily, already scouting for his next piece of treasure to hoard.

By our fourth day stuck in the ice, I already knew everyone on board hated me. No one spoke to me, which was impressive, considering there were only three others. Our captain never offered me tea or bothered to teach me how to play cards. The marine biologist never showed me her sketches. Not even our cameraman, who’d made it loud and clear that he could’ve been spending the winter snapping mountain goats in Northern Italy, didn’t consider me much of a shoulder to whinge on. And I was alright with that. When you spend your life broadcasting messages across oceans, it’s easy to become distant from those closest to you.

Our first real fight broke out that fourth evening. I should’ve seen it coming. As usual, I was leaned back against the canteen wall, listening to the cameraman and the marine biologist chat over their rations of salt cod.

“I heard it again last night, Rose. I’m telling you it’s got to be a whale.”

The biologist sighed and shook her head, “That’s no whale, kid.”

“Yeah. Couldn’t be,” I chipped in from my corner through a mouthful of salt and flesh full of needle bones. “Too cold for whales.”

The conversation was cut short by the clanging of approaching boots. I saw the chalky white fragments in the captain’s hand, and I saw the scowl on his face. I cringed, my spine pressing hard into the cold wall.

“You little rat!” He dove at the cameraman. The young man ducked – but the captain’s palm laid open, intending to show rather than to strike. “See what you’ve done to my scrimshaw!”

“I didn’t mean to! I didn’t mean to!” the cameraman babbled, lifting his palms. “I swear, I didn’t even see it there!”

“You idiot!” the captain hissed, laying the pieces out on the table. “Do you have any idea what I traded for this thing?”

I half-watched him sift through the pieces. I’d never seen the full thing up close before, so I didn’t know what he was trying to put back together. The splinters of etched tooth, swimming in the canteen’s dim light, could have represented anything I wanted them to. Narrowing my eyes, I made myself see the twists and turns of a great, submerged frame in the carved enamel. The broken outlines became grasping hands, fractured eyes. Bony spines, tentacles. All those things at once and more. And then, nothing at all. Only a mass of broken tooth on an old table.

I stayed up that night. Waiting. Casting calls for help out into the frozen waves. Listening for an answer. It must have been past midnight when I heard the cameraman still awake. I got up and went to tap at his matchbox of a cabin. Somewhere inside, a quiet sobbing.

“Ted?” I called, tapping again. “Ted, it’s me. Are you alright?” I sighed and leaned against the wall. “Look, I know we haven’t exactly been the best of friends so far, but if you need –”

His sobs warped into a terrified wail. It vibrated through the wall, through my hand, striking through the frozen frame of the ship. Through the weeping I spoke to him, though I knew he would not listen. We would only be out here for a couple more days at the very most, I assured him. Yes, it meant he wouldn’t find what he’d come so desperately seeking. But the surface world would understand. They’d understand.

The next morning, I hung around under the canteen portal and watched the marine biologist try to tack together broken pieces of ivory.

“Well, there goes our only artist’s depiction,” she sighed, rubbing the dark hollows under her eyes. “Our only real biological sample, too.” This time, it was my turn not to respond. I only stared with bleary eyes through the three-inch glass separating the inside of the hull from a frozen saltwater void.

“He hates me. He hates me. He hates me.”

I almost jumped. I hadn’t spotted him down there. The biologist sighed, put down her tube of glue, and looked down at the cameraman, curled up on his side at the foot of the table.

“Ted, don’t talk like that. No one hates you.”

Her hand came to rest on his slumped shoulder. His wide, bloodshot eyes rose to meet hers.

“It hates me. It hates all of us. It wants us dead.”

“Ted…”

“I heard it again.” His stiff, twitching fingers caught the sleeve of her sweater and strangled it. “Screaming. Moaning. Like… like something trying to get in.”

“It’s just… just whalesong,”she muttered. “That’s all. Whalesong.”

“I’m telling you, it’s not a whale.” I grumbled. Neither of them so much as looked up. So I didn’t look at them either. I just looked at my reflection, a drowned ghost in the dark glass.

“It’s my fault that it’s broken,” whimpered the cameraman. “First the radio. Now this. No one’s coming. There’s nothing out there to hear us.”

“Yes there is,” I hissed through the cold, “Yes. There. Is. We just have to keep calling. Keep listening.”

But as usual, no one heard me. And I was left staring through the glass once again. Running my tongue through the gap left by a missing tooth.

They can keep shutting me out. That’s fine. I’m used to it. But I wish they’d at least look out of the window once in a while. It’s so, so cold out here, and I don’t know how much longer I can keep calling, listening, treading water.

It hadn’t been at the dock when the townspeople went to bed. It must have come in with the storm that had passed through that night. It was like nothing anyone had ever seen before. It wasn’t made out of wood like their ships and boats, but a material that reflected the sun like a mirror. A small crowd had gathered, but no one dared approach the vessel.

A door opened and a man stepped into view. He had long gray hair and a gray beard. That’s where his similarities to the crowd ended. His breeches only came to his knees, and his shirt was covered in bright flowers of various colors. His shoes were open, exposing his whole foot and held together with nothing but some straps. As the man came off the vessel onto the dock the crowd backed away. He was as strange looking as the vessel he had just stepped off of.

“Hi there, folks,” the man said. “I’m Austin. Could you tell me where I am? Got caught in a bad storm last night and have no clue where I ended up.”

“You are in East Hampton, sir,” a man told him.

“East Hampton? So I didn’t stray too far. Never been to his marina before,” he said looking around. “Are you folks doing a reenactment or something?”

The confused townspeople exchanged looks.

“A reenactment?”

“You know, a reenactment. Pretending to be people from like 1775 with those funny outfits.”

“We are not pretending anything. And if any clothing is funny it is yours,” said a young man stepping forward. “Where are you from?”

“I’m from here. ‘Cept I’ve never been to this part of East Hamptom before,” the strange man said.

“We have never seen you before,” the young man said. “And we know every person who lives here. What is this vessel of yours?” The man approached it and ran his hand over it.

“This here is a 2025 NAVAN C30. This is my first time taking her out,” the man said, patting the vessel.

“But what is it?” He asked.

“What do you mean what is it? It’s a boat. What more is there to it?”

“This is a . . . boat?” the young man asked, not quite believing Austin.

“Well of course it is. Wha’d ya think it was? A rocket? What’s your name, son?”

“Benjamin,” he told the stranger. “I have never seen such a vessel before.”

“Do you mean to tell me you’ve never seen a boat like this before?”

“No sir, I have not.”

“Well I’ll be! I didn’t know there were still backwater places around here. Feel free to climb aboard and take a look.”

Austin helped Benjamin onto the boat.

“This here is where you start the engine.”

Austin turned the key, and the sound startled Benjamin and the others on the dock.

“Want to go for a ride?” Austin asked Benjamin.

“No Benjamin! Do not go anywhere on that vessel!” A woman said, fighting her way to the front of the crowd. “Come off of it now. Please!”

“Do not worry, mother. I will be alright,” Benjamin told her. “Please show me how this works.”

Austin took the boat out into the open water. Benjamin let out a gasp as the boat took off, and the people on the dock screamed as they were soaked by the wake. As Austin took the boat into the open water he looked back at the land and saw nothing but trees. Confused, he turned to Benjamin.

“Where in East Hampton am I, Ben? Where are all the beach houses?”

“Beach . . . houses? All the houses are in the village.”

“This makes no sense. This boy doesn’t seem too bright,” Austin murmured to himself.

All of a sudden, out of nowhere, a storm blew in.

“Where did that come from?” Austin yelled to Ben as the wind picked up. “You’d think this boat attracts storms. Hurry, get below!”

Austin ushered Benjamin into the lower part of the boat.

“What is all this?” Benjamin asked, looking around the room with his jaw hanging down.

“This is the living quarters. Got everything I need down here. Stove, fridge, bathroom. Impressive, aye?”

“Stove? Fridge?” Benjamin looked at Austin like he was speaking another language.

“Don’t tell me you don’t have a stove and fridge in your house! Do you have no modern conveniences?” Austin mirrored Benjamin’s astonishment.

“I do not know what you are speaking about,” Benjamin said. “It’s like you are from another world.”

Benjamin slowly lowered himself onto the couch, not taking his eyes off of Austin. Austin tossed a book onto his lap.

“Read this so you can learn what a boat is.”

Benjamin looked at the book with a picture of a vessel similar to Austin’s on the cover.

“How did the artist get this painting to look so real?” Benjamin said in awe.

Austin crawled onto the bed with a book of his own mumbling to himself. After about an hour he felt the waters starting to calm down.

“Sounds like the storm has passed,” he told Benjamin. “Let’s get you back.”

The two men went back out to the top of the boat. The storm had pushed them closer to land, and Austin saw the marina he had left from the day before full of boats.

“We’re back at my marina! Thank goodness,” he said.

Austin looked over at Benjamin and saw the shock on his face that had turned white.

“What’s the matter, boy?” Austin asked him, studying his face.

“How is this possible? What is this?”

“This is the East Hampton Marina. I can’t believe you’ve never been here before. Who would have thought in the year 2025 there would be someone who has never seen a real boat before.” Austin said.

“What do you mean 2025? The year is 1778.”

The two men stared at each other, each wondering if they were dreaming, mad, or if the impossible had happened.